“Only from the heart can you touch the sky.” – Rumi

She was born Mary Granville in 1700 at her father’s country house in the Wiltshire village of Coulston. Hers was a well-to-do English family. She would hear first-hand the voyage of Captain Cook and be astonished by that voyage horticultural bonanza. She would attend her hero Handel’s Messiah. She would flirt with Jonathan Swift.

She married at age 17 and was widowed at age 21. She joined the Blue Stockings Society which was a revolutionary women’s social-educational group that supported intellectual pursuits.

With a life-saving combination of propriety and inner fire, she designed her own clothes, played the harpsichord, took drawing lessons, owned adorable cats, and wrote six volumes of letters most of them to her sister.

She later wed Dean Patrick Delaney, a Protestant Irish clergyman. She bore no children. They lived on an 11-acre estate near Dublin where Mary began her shell decorations and crewelwork. She made a spectacular leap from what she saw and what she cut four years after Dean’s death.

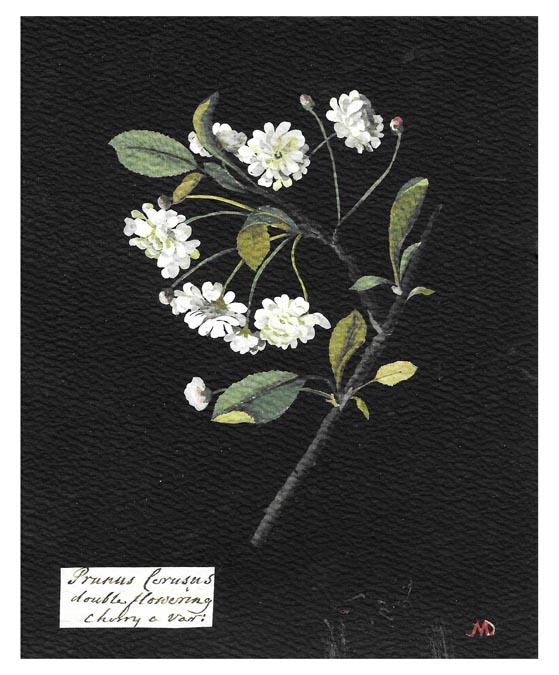

Mary was 72 when noting the likeness between a geranium and a scrap of red paper she began the first of her 985 “paper mosaicks.” Of the practice she wrote, “I have invented a new way of imitating flowers” She built up her specimens sculpturally, cutting minute bits of paper into as many as two hundred petals, layering small pieces over larger ones for contour and depth and adhering them likely with egg white or flour paste to solid black backgrounds The results were elegant, intricate and botanically accurate, and became so popular that King George III ruled all curious or beautiful plants be sent to Delany upon blossoming.

She had entered a mesmerized state induced by close observation. Have you remembered the atmosphere of a time long gone, but now present and almost palpable to the touch? She used tweezers, embroidery tools, various brushes, pieces of old glass, honey and paint. As it was a feast for the tactile senses, but it was dirty, smelly, and prodigious.

Mary Delany always had been an artist, but during her second marriage, she had the time to hone her skills. She was a gardener, a botanist, did needlework, drawing, and painting, but was best known for her paper-cutting. In 1771 she began on decoupage, a fashion with ladies of the court. Her works were detailed and botanically accurate depictions of plants, using tissue paper and hand colouration.

Those mosaicks are coloured paper representing conspicuous details, but contrasting colours or shades of the same colour so that every effect of light is caught. With a plant specimen set before her, she cut minute particles of coloured paper to represent the petals, stamens, calyx, leaves, veins, stalk and other parts of the plant and formed the shading with light or dark paper. It is thought that she first dissected each plant so that she might examine it carefully for accurate portrayal.

Mary worked until her eyesight failed in 1788, the final year of her life. Death approached on April 15, 1788. A memorial to her was placed at St. James’ Church in Piccadilly.