By Tom Siebert

“Nothing affected me until I heard Elvis,” John Lennon once said. Bob Dylan described hearing Presley’s voice for the first time as “like busting out of jail.”

I grew up in a subsequent era, however, when the “King of Rock ’n’ Roll” was widely viewed as an aging Vegas crooner who had long left the building of musical significance.

But when I watched director Baz Luhrmann’s television epic, Elvis, I was caught in a trap for 159 mesmerizing minutes, making me astonishingly aware that Presley’s life was much more triumph than tragedy.

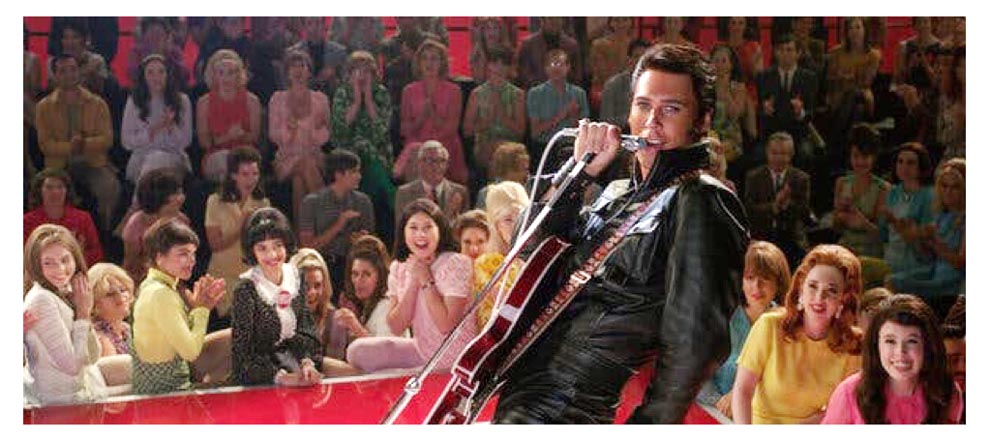

In a tour de force performance, newcomer Austin Butler completely inhabits the hip-swiveling, barrier-breaking international supernova of music, movies, television, and time present.

Seen in dizzying flashback through the dying eyes of Presley manager Colonel Tom Parker, played by a puffy, prostheticized, Tom Hanks, Elvis is more of a fast-moving montage than a movie.

The sweeping, frenetic film slows down just enough to depict in riveting detail Presley’s poverty-stricken beginnings in Mississippi, early rockabilly recordings, audiences of screaming girls and seething boys, mediocre-but-money-making films, dutiful Army service, stunning television comeback shows, and final glide path to drugs, womanizing, gun-wielding paranoia, and world-mourning death.

The movie has been praised for its overall accuracy by Elvis’s ex-wife, Priscilla, and daughter, Lisa Marie. But screenwriters Luhrmann, Sam Bromell, Craig Pearce, and Jeremy Doner did take some dramatic license.

Although it is true, for instance, that Presley’s sexually suggestive stage mannerisms garnered the attention of law enforcement, there is no documented evidence that Colonel Parker made a deal with the U.S. government that sent Elvis into the service in exchange for no criminal charges being filed against him.

What’s more, or less, no one in Elvis’s living circle can recall his hanging out with B.B. King and receiving career advice from the blues guitar great, as was imagined in the movie.

Besides, it would have been much more fun to fabricate Presley’s cavorting with Chuck Berry, who may not have invented rock ’n’ roll but certainly wrote its early narrative of teenagers, jukeboxes, malt shops, and sock hops.

A reincarnated Little Richard does appear in the film, portrayed eerily accurately by Alton Mason, who sings “Tutti Frutti” with all wail and glory.

However, it is easy to believe that Elvis was indeed profoundly affected by the assassinations of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy.

It would explain his dramatic shift from the good-rocking “Hound Dog” and “Heartbreak Hotel” to message songs such as “In the Ghetto” and “If I Can Dream,” the brilliant close to Presley’s NBC-TV special in December 1968 after the scrapping of a cheesy holiday medley.

But by far the most controversial aspect of the movie is the world’s top actor, Hanks, playing Parker as a gambling-addicted demon who exploited Elvis commercially, personally, and fatally.

“I made Elvis,” Parker said near the end of the emotionally exhausting film. “But I didn’t kill him.”

No, he did not. And according to Parker’s biographer, Alanna Nash, there is no truth to the high-anxiety scene during which Presley fires his manipulative manager during a concert at the International Hotel in Las Vegas.

There is no question, however, that Parker’s 50% cut of Elvis’s earnings, coupled with the rigorous performing schedule that the manager demanded, played an integral part in Presley’s rise and fall.

But the singer’s exciting, operatic voice, as well as his ingenious blending of blues, gospel, and country music, would have eventually changed the course of culture, even without the help of a conniving carnival barker.

When the 42-year-old entertainer died of heart failure at his Graceland mansion in Memphis August 16, 1977, Elvis’ net worth was $5 million. His estate since has risen to an estimated $500 million, to make him the most commercially successful solo act of all time.

This movie, moreover, already has made more than $220 million, the second highest-grossing musical biopic behind 2020’s Bohemian Rhapsody, the story of Queen front man Freddie Mercury.

I went to see Elvis in suburban Chicago with members of my Christian singles group, a redemptive twist, considering that many churches, particularly in the South, once condemned Presley’s songs as “devil music.”

To paraphrase Dylan, the times they have a-changed. Elvis is perhaps the biggest reason.