When Chicago was incorporated in 1837, residents could walk anywhere in the small frontier settlement. For much of the 19th Century, Chicago was the world’s fastest-growing city. Chicago was the place where the future was unfolding. The City was brash and bold and would see the electric trolley in 1890 and the elevated (“L”) in 1892.

The first successful alternative to horse power in Chicago was the cable car. It ran twice as fast, but cost only half as much to operate. The cable car came to Chicago in 1882. Transit baron Charles Tyson Yerkes converted his major horse car lines to cable from 1887 to 1893. The city then had 1,500 cable cars. There were 11 power stations and 86 miles of track which made it the biggest cable car system in the world.

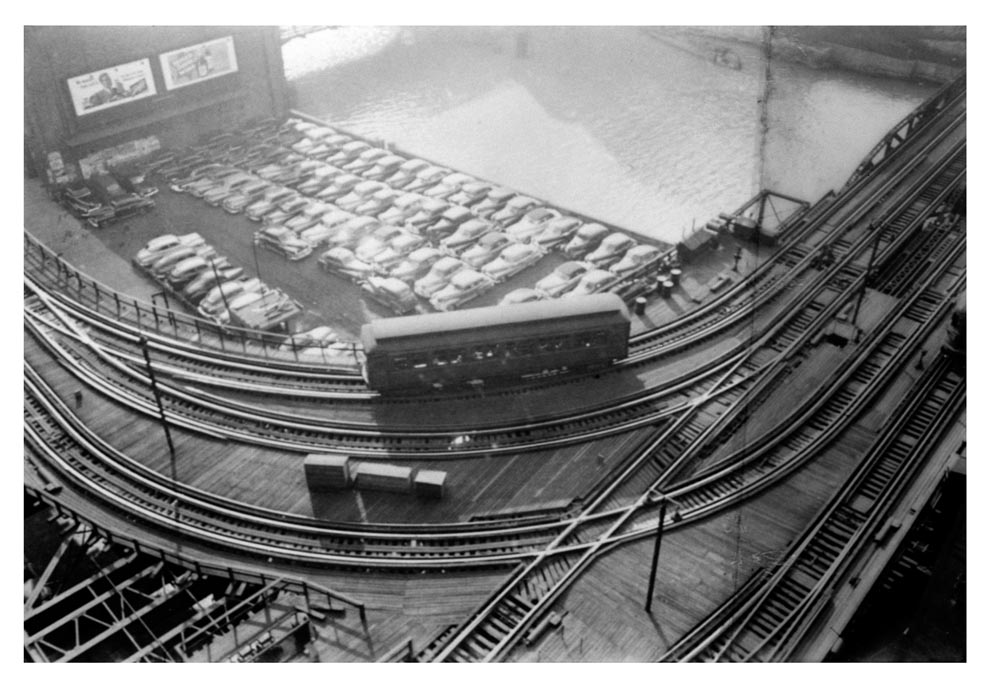

Four “L” lines were built. Construction cost $500,000 to one million dollars per mile, now about $12 to $24 million per mile, adjusted for inflation. These served as the backbone for additional lines over the next century and created one of the world’s greatest transit systems.

The “L” carries half a million riders each day and most of them move swiftly and safely. It enhances property values along its routes. It is worth untold billions of dollars. Today it includes 1,200 rapid transit cars carrying 160 million passengers each year on eight lines serving 144 stations covering more than 222 miles of main-line track.

The U.S. Congress in 1890 voted to hold the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The City put the fair in Jackson Park on the Southeast Side. Plans were drawn up to extend the “L” south to 63rd Street. Chicago’s first “L” operated with steam locomotives. In 1892 those 20 little engines that could left the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia for Chicago.

The new line ordered 180 wooden passenger cars. They were beautifully crafted with gold leaf trim, mahogany interiors, slatted shades, gas laps, a canvas-over-wood roof and colored-glass ventilator windows. One is now on display the Chicago History Museum. Those first trips cost five cents and took 14 minutes. The South Side “L” carried more than 12 million passengers to the Fair. The Fair was served by cable cars, electric trolleys, shore boats, and main-line railroads.

Even in 1889 there were contract disputes, funding issues, political maneuvering, and access to the business district was contentious. With intensive lobbying and some bribes, permission was given to build the downtown over Market Street (now Wacker Drive) and a lawsuit from a competing streetcar company which interrupted construction several times on the Lake Street “L”. Market Street was wide and full of factories. By 1903 financial issues had caught up with the Lake Street “L” and the company went bankrupt. Some considered it risqué for unacquainted men and women to sit side by side in such an intimate unchaperoned setting as the longitudinal “L” seats. Imagine!

By the end of World War II, the “L” was on the brink of disaster. During the Depression, ridership had declined and the system deferred critical maintenance. So April 12, 1945 the Illinois legislature created the CTA as a municipal corporation to acquire, operate, and unify all mode of local transit.

The CTA purchased all modes of transit to integrate disparate services and eliminate wasteful competition. The “L” has been called “the city’s rusty heart.” The “L” is both old and dynamic. The Loop structure and dozens of stations are officially designated historic landmarks. The cars were painted red, white and blue to celebrate the Nation’s bicentennial in 1976. They were named after Revolutionary War heroes, including locally popular figures.