By Brendan Bond

(From February 14, 2013)

Seventy years ago this month, the battle of Stalingrad officially ended, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was named commander of the Allied armies in Europe, and the U.S. scored its first offensive win of the Pacific Theatre at the island of Guadalcanal.

The history of the Second World War has been written in the figures such as Eisenhower, Hitler, and Churchill. It has been told with military maneuvers such as the Blitzkrieg and the landing at Normandy. Dates such as December 7, 1941 and June 6, 1944 are memorized in grade school.

But the real history of World War II is told in the stories of those who lived through it. The soldiers. Their mothers. Those in the internment camps. The citizens who lived under Nazi rule.

Beluse Zidlicky is now 83 years old and resides on a sprawling farm in Oswego. Her story of coming to America is that of many. The fear and eagerness she had before arriving in New York City. The promise of the new country and the struggles she went through trying to build a new life for herself. It’s the story of many immigrants.

The difference in Beluse Zidlicky’s tale of how she came to America is what she went through in the decade-plus before she arrived in the United States April 2, 1952.

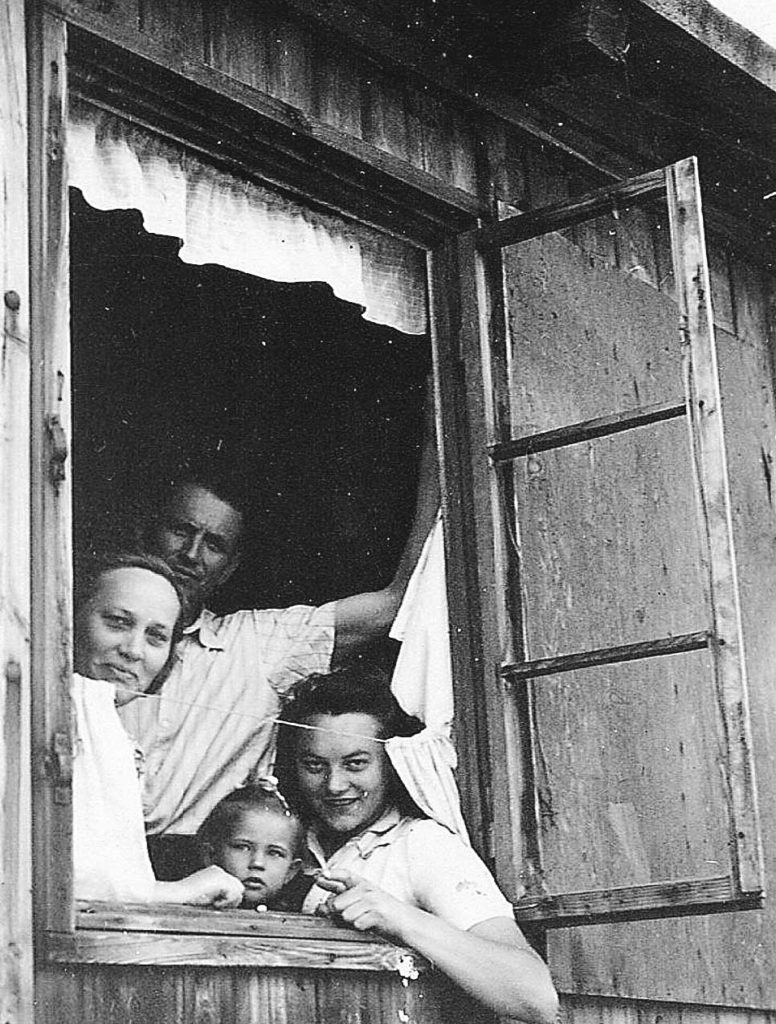

Beluse was the eldest of three children born to Frank and Antonie Ulrich. Her birth name was Beluse Ulrich and she was born in 1929 in Kozomin, Czech Republic, a village to the north of Prague. Back then, Czechoslovakia was one nation. Growing up, Beluse lived in Bratislava, currently the capital of Slovakia, and Tornala, another town, that is currently in Slovakia.

The Ulrichs moved to Prague in 1937. By this time, Beluse had one younger brother, Zdenek, who was two years younger than she. Another brother, Miloslav, was born in Miloslavo near Bratislava.

The Nazis began occupying parts of Czechoslovakia in 1938 following the Munich Agreement and it wasn’t long before the entire country was under the control of Hitler.

Beluse is assisted by her son, John, recently in retelling her tale, but memories from more than 70 years ago still appear clear to her.

“It used to be like paradise,” she said when describing her homeland before the Nazi takeover.

“It was scary when the Nazis first walked through,” she said. “But for the most part they left you alone. They just wouldn’t let us go to school.”

Beluse said that they would huddle around the radio during the war and listen to the “Voice of America,” a radio broadcast that began during the war and was transmitted into nearly 40 languages. The broadcast would bring the happenings up to date of the war from the Allied perspective.For those such as Beluse under Nazi control, the future arrival of the Allies was the glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. The Allied planes would fly overhead on their way to attack Germany and Beluse and her friends and family would go outside to watch.

“We would count the bombers going over our heads, then count those who were coming back to see how many were missing,” she said.

Eventually, when it became clear that the tide of the war had turned and the end was nigh, the Nazis became more hostile. In 1945, Beluse’s cousin, Milka, had her husband and two brothers arrested by the Nazis for allegedly assisting revolutionaries. The three men were forced to dig their own graves, then were shot, and killed in them.

Beluse lived on a farm near a private girls’ school where the Hitler Youth had been stationed during the war. At the end of the war, the Youth would not leave and barricaded themselves inside the school. The youth killed 11 individuals before a German soldier was forced to carry a white flag and told them to surrender. One of the individuals killed was a Czech policeman who took a position in the second floor of Beluse’s family’s barn thinking that he could snipe the Hitler Youth members.

Finally for Beluse and her family, though, the Allies won the war and the Soviets came through to liberate the region.

“I felt sorry for the tired, dirty Russians when they first came,” Beluse said. “They would steal stuff, but they were nice.”

Once the Soviets arrived, all of the those who had been taken by the Nazis to the concentration camps came back and Beluse got to see first-hand the effects of the horrors of those camps.

“The people coming back from the concentration camps were all skin and bones. You could see only eyes,” she said.

After the war ended, Beluse and her family moved from Prague to a farm in Lazne Libverda. Although they changed their living arrangements, the control of Czechoslovakia changed from Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union. Beluse went from one form off oppression to another.

For three years, they spent life under Soviet control while Western Europe began to thrive again. Then, in February 1948, her father, Frank, who was politically active and outspoken, was arrested the day before a communist coup occurred in the country. Along with being outspoken, he was deemed a flight risk. That’s why he was arrested.

After his arrest, authorities told Beluse, her two brothers and their mother that the family had two hours to get out of the house. Beluse remembered that it was a cold and snow-filled day, but the Soviets had no concern for how the weather would affect the now-displaced and disrupted family.

Everyone was afraid to take them in for fear of upsetting the government. Finally, one neighbor took them in and that’s where they stayed while her father was imprisoned.

Beluse and her mother went to the mayor to ask for their stuff back. In the haste to leave their home, much of their possessions were left behind and seized. The mayor ruled that they had to go to a county official to ask.

It took a whole month to hear back, but finally the official gave them written permission on a piece of paper to give to the mayor. Upon bringing that paper to the mayor, however, he ripped it up in front of the Ulrichs.

“He said, ‘I’m the boss,’” Beluse said.

Frank was let out of prison after six months and immediately attempted to take back his family’s possession. He rented a truck and went to get them, but the mayor intercepted him and forced him to leave the possessions alone.

Determined, Frank waited until the mayor was gone one day. The Ulrichs went to sneak their possessions away from control. After doing that, though, the neighbor who took them in got nervous that the mayor would seek revenge. His wife kicked Beluse’s family out of the house, prompting them to move to Beluse’s aunt’s farm in Dubice, a countryside village in the north of Czechoslovakia.

Here, Beluse’s father began plotting ways to get people out of Czechoslovakia and into West Germany where they would be free.

He took a job as a log-runner who spent time in the heavy woods that stood between the Czech countryside and Germany and acquired a team of horses. He came up with the idea of inserting a false bottom in his wagon as a way to hide escapees.

The whole idea of escaping from land under Soviet control was a dangerous one. There were no walls similar to the one that later existed in Berlin, but there were guards that patrolled the area and would sometimes cross over the border to capture runaways. Lots of individuals were shot when attempting to escape.

But Frank did his job as a transport for escapees very well. According to Beluse, he helped her future husband and many others escape by driving them to the forest in his false-bottomed wagon where he could squeeze in up to four persons.

“Just like sardines,” Beluse said with a smile.

The Ulrichs, early in 1950, moved to Tachov, which was on the western edge of Czechoslovakia, not far from the West German border. They began planning their own escape.

It occurred in July 1950. Over the course of two days, the family managed to make it across the border, but not without coming close to getting caught when her father was questioned once by guards. The family reached safety in the town of Bärnau, Germany, where they stayed for two days before continuing their westward travels, this time to Nuremberg.

Once the family was safely in Germany, they grabbed their paperwork and were sent to Valka, the refugee camp for Eastern Europeans in Nuremberg. Along with five other families, they were crammed into one house where they stayed for 18 months. They had bedbugs to contend with, but they were no longer under Soviet rule.

At Valka, Beluse had a monthly allowance, but had no work. She spent her time meeting others at the camp who were from numerous countries that came under Soviet rule following the end of World War II.

During the 18 months there, the goal was for the family to achieve emigration status to another country. Frank was a farmer and initially applied to countries that were willing to take farmers, including Canada, France, England, Venezuela, and Argentina.

At Valka, lists were posted of which country would take which person, very much like sports team registrations.

Eventually, her father was not chosen as a farmer but was selected to move to the United States. Beluse, though, was accepted to go to Canada with her cousins and Zdenek Zidlicky, her future husband. In the end, she made the decision to accompany her parents and family to the United States.

The family set sail after getting accepted to the United States. That news reached them around Christmas 1951.

“It was the best Christmas gift ever,” Beluse said.

They left from the port city of Bremerhaven on the North Sea and took an Army ship route, passing through the English Channel. Recalling the memory, Beluse distinctly remembered seeing the Cliffs of Dover in the distance.

They didn’t see much else on their voyage though. They saw no other ships and did not come in direct contact with any storms. However, because of weather systems in the area, the waves were monstrous and caused a lot of seasickness on board the ship.

“They were like black mountains,” Beluse said of her memory of the rolling sea and the huge waves.

The Ulrichs eventually arrived in the port at New York City at the beginning of April 1952.

Just like many immigrants, one of their first views of their destination was the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor.

“It looked a lot smaller in person,” Beluse said.

After that comment, though, Beluse was at a loss for words in reflection when trying to explain the emotion of reaching the United States. She became emotional and her son, John, pitched in, saying that words could not describe how it felt.

The Ulrichs were overwhelmed at first. New York City was bigger than anywhere they had been and they felt like they were still moving, not having adjusted from the sensations they felt from being on the boat for so long.

To add to the confusion, the Czech consulate didn’t know they were coming and, as a result, didn’t receive them.

The Ulrichs ended up taking the subway in New York City and went around on it forever because they didn’t know where to get off.

But they survived that, just as they did the struggles in Europe, and they were soon bound for Chicago by way of bus. In April 1952, seven years after the war in Europe ended, the family arrived in Chicago.

They got an apartment in the Czech neighborhood on 26th Street on the southwest side of the City, but the family eventually moved into a house six months later, in Berwyn, a near west Chicago suburb.

When the family was in Chicago, Beluse had two men she loved living in Canada. Milo, her brother, was working there with a farmer and even had his appendix removed while north of the border. Zdenek, her future husband, was living in Canada.

It took Milo a year to reunite with his family. Meanwhile, Beluse had to go to Pickering, Ontario, just outside of Toronto, to court Zdenek and marry him. Once married, they were able to move back to the United States.

Now a Zidlicky, Beluse and Zdenek moved around Chicago before purchasing a three-and-a-half acre farm in Villa Park. Eventually, a family grew and the Zidlickys kept upgrading, to a 15-acre farm, then the current 300-acre farm in Oswego.

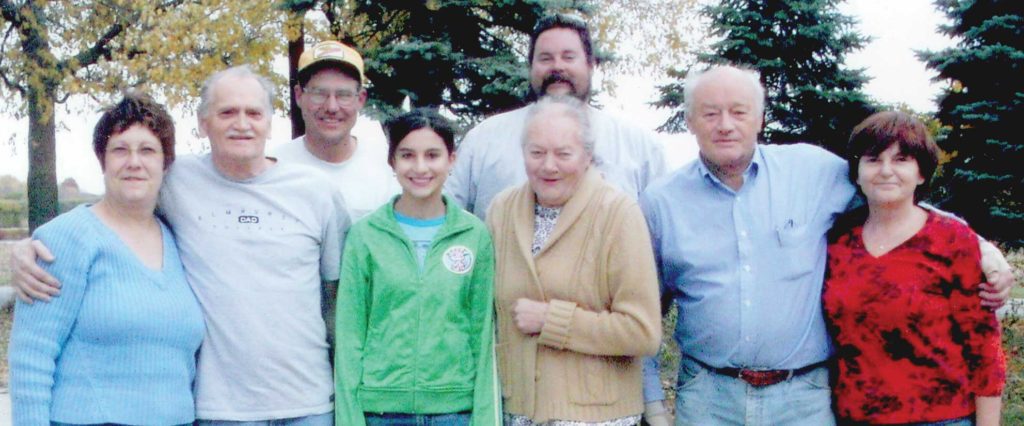

Beluse and Zdenek raised three children, two boys, John an Zbynek, and a daughter, Zdenka. There are six grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Her late husband, Zdenek, died August 5, 2005.

Beluse has come a long way since watching the U.S. bombers flying overhead. But she knows she’s been blessed while many she grew up with were not. That is why she struggles with the attitudes of many Americans.

“Americans are wasteful and need to appreciate what they have more,” Beluse said. “Don’t take everything for granted.”