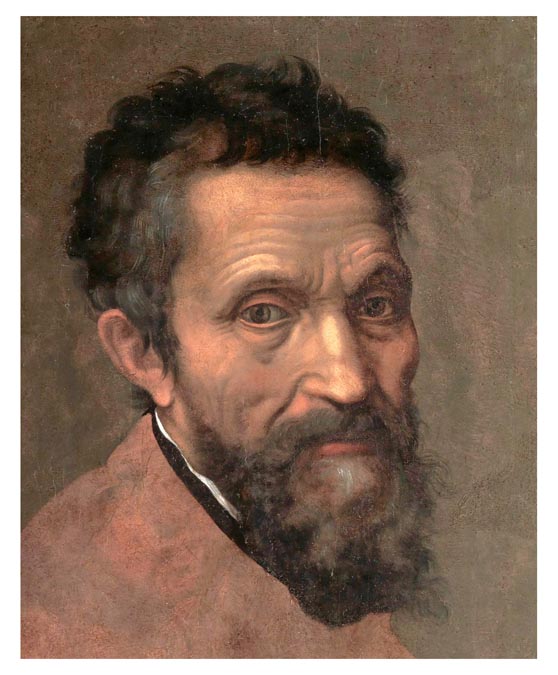

In his lifetime, Michelangelo was called Il Divino, or, “the Divine one.”

He was born March 6, 1475 in the Republic of Florence. For several generations his family had been bankers in Florence, but the bank failed and his father, Ludovico, took a government post in Caprese. Several months after his birth, the family returned to Florence. His mother died when he was six years old. He went to live with a nanny and her stonecutter husband. There he gained his love for marble.

As a young boy he would copy paintings from churches and liked to be in the company of other painters. Florence at that time was Italy’s greatest center for arts and learning. In November 1497 the French ambassador to the Holy See (Church government), commissioned him to carve a Pieta, a sculpture showing the Virgin Mary grieving over the body of Jesus. Michelangelo was 24 years old at the time of its completion.

It soon was to be regarded as one of the world’s great masterpieces of sculpture. It was “a revelation of all the potentialities and force of the art of sculpture,” Vasari said. “It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.” It is now in St. Peter’s Basilica. When I saw it in 1979, it was open to be seen. Later, a glass shield was placed to protect it.

Two of his best-known works, the Pieta and David, were sculpted before his age of 30. He created the influential frescoes with the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome. At the age of 71, he became the architect of St. Peter’s Basilica.

The first half of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was completed in July 1510. The Sistine Ceiling is a raging tempest in which God is no longer a comforting presence, but a surging, disruptive, power. Those who are witness to His Creation were tossed about by forces beyond their comprehension, “Agitated, enlightened, or ecstatic the revelation courses through their bodies like an electric current,” was one comment.

When Michelangelo was 75, he became preoccupied with thoughts of death, and second-guessed his chosen path and agonizing over his own salvation. The pride he once took in worldly success had been exposed as vain illusion. “I’ve reached the end of my life’s journey,” he wrote in one of his final poems.

Despite physical exhaustion and bouts of melancholy, Michelangelo still burned with creative fire. He wrote that, “If the pains I endure profit not my soul, I am wasting my time and my work.” With another commission from Pope Julius II, he began work on a new church at the heart of the Vatican with a new, more magnificent, edifice. The Church marked the spot where Peter, Prince of the Apostles, and first pope was buried. The pope was determined to leave his mark on the city he had grown up in and work crews once again swarmed the area behind the half-dismantled, old, basilica.

Michelangelo died early on the evening of February 18, 1564. News of his death was greeted with mourning in Rome and his native Florence, as well, as in the courts and capitals of Europe. His physician described him as, “the greatest man the world has ever known.”

The hagiography began almost at once and replaced the flesh-and-blood reality of, “a flawed, tormented, man with the pale ghost of a secular saint,” according to one eulogy.

After five centuries, the works he left behind offer, “something more nourishing than the faint perfume of sanctity. They throb with the earthy, pulsing, difficult stuff of life,” was another eulogy.