“To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny, or delay, right, or justice.” Clause 40

In 1206 King John renewed his war with France causing him to lose the duchies of Normandy and Anjou among other territories. A feud with Pope Innocent III began in 1208 and further damaged John’s prestige. He became the first English sovereign to suffer the punishment of excommunication.

After another embarrassing military defeat by France in 1213, King John attempted to refill his coffers and rebuild his reputation by demanding scutage (money paid in lieu of military service) from the barons who had not joined him on the battlefield. The archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, channelled baronial unrest and put increasing pressure on the king for concessions.

Thus the stage was set after years of unsuccessful foreign policies and heavy taxation demands.

England’s King John was facing a possible rebellion by the country’s powerful barons. Under duress he agreed to charter of liberties known as the Magna Carta, or Great Charter, that placed him within a rule of law.

Eventually this document served as the foundation for the English system of common law. Later generations of Englishmen celebrated the Magna Carta as a symbol of freedom from oppression. So did the Founding Fathers of the United States, who, in 1776, looked to the Charter as an historical precedent for asserting their liberty from the English crown.

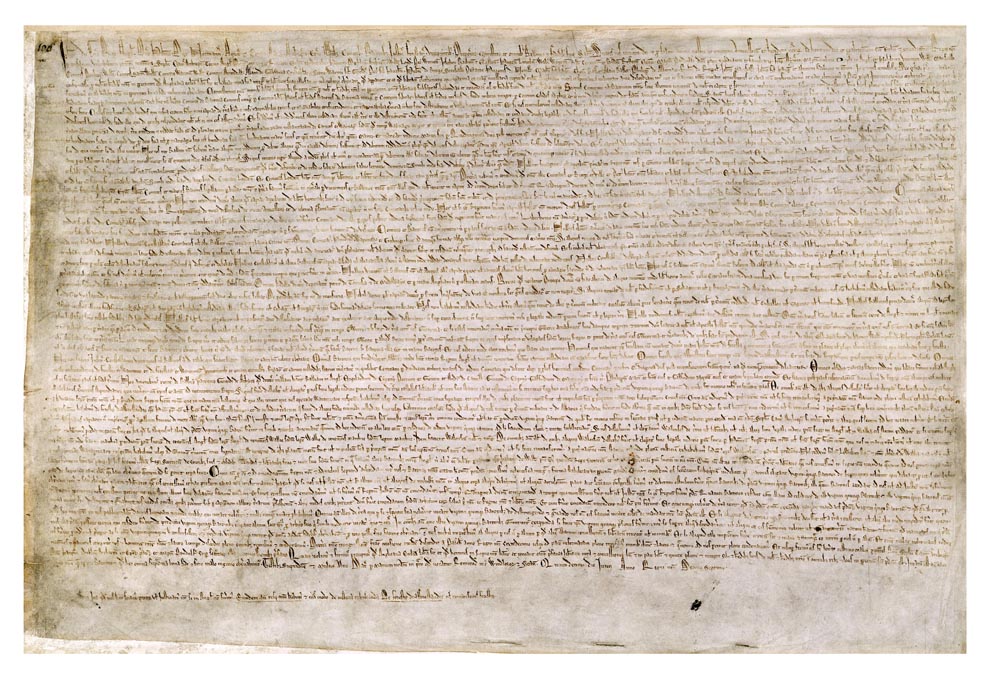

Written in Latin, the Magna Carta was effectively the first written constitution in European history. Of its 63 clauses, many concerned the various property rights of barons and other powerful citizens. Those benefits were for centuries reserved for only the elite classes, while the majority of English citizens still lacked a voice in government.

June 15, 1215 at Runnymede, which was beside the River Thames, now in the county of Surrey, the king met with the barons. King John accepted the terms included in a document called the Articles of the Barons. Four days later, after further modifications, the king and the barons issued a formal version of the document.

Key provisions of the Magna Carta include: Habeas corpus, known as the right to due process, said that free men could only be imprisoned and punished after lawful judgment by a jury of their peers. Justice could not be sold, denied, or delayed. Civil lawsuits did not have to be held in the king’s court. If the king wanted to call the common council, he had to give the barons, church officials, landowners, sheriffs, and bailiffs, 40 days’ notice that included a stated purpose for why it was being called. Bailiffs and constables could not appropriate people’s possessions. The king could not have a mercenary army. In feudalism, the barons were the army.

Until the Magna Carta, British monarchs enjoyed supreme rule. The king, for the first time, was not allowed to be above the law. He could not abuse his position of power.

There are four known copies of the Magna Carta today in England. In 2009 the four copies were granted UN World Heritage status. Two are at the British Library, one is at Lincoln Cathedral, and the fourth is at Salisbury Cathedral. A copy can be seen at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., along with the U.S. Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution and U.S. Bill of Rights.

Today, memorials stand at Runnymede to commemorate the site’s connection to freedom, justice, and liberty. In addition to the John F. Kennedy Memorial, Britain’s tribute to the 35th U.S. president, a rotunda built by the American Bar Association stands as a tribute to Magna Carta, symbol of freedom under law.