“Terrible as an army with banners the legions of labour

the builder of ships tramp thro’ the winter eve.” —Richard Williams

It was a blustery Belfast, Northern Ireland December morning, 1979, when I had appointments with the workers at the Harland & Wolff shipping yards. My friend and driver, Jim, had arranged this interview for me and we walked into a wee office to meet several of the men who worked on building the Titanic.

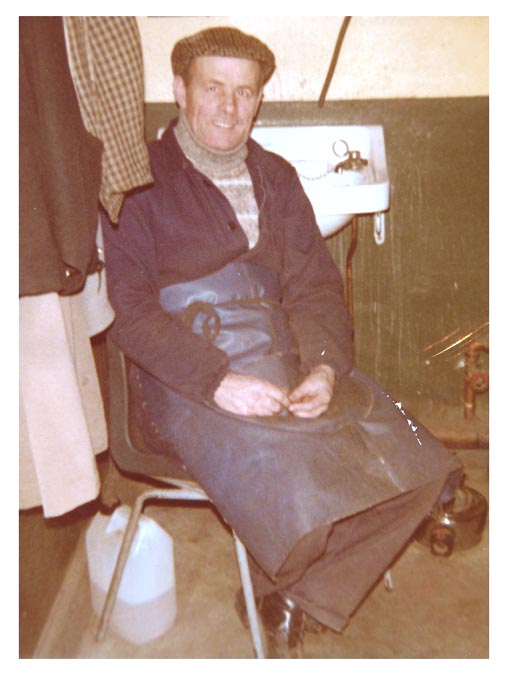

They were a rough looking bunch holding their coffee cups and leaning against the desk. Long hair. Whiskers. Heavy sweaters to ward off the Belfast cold. They were anticipating an early off because the Company’s Christmas party would begin shortly. They knew they would receive an envelope with British pounds in each one as their Christmas bonus. We talked and I took photographs. Now if only I could find those images!!

Harland & Wolff was founded in 1853 by Robert Hickson who sold it to a man “answering a newspaper ad for shipyard manager.” That man was Edward Harland who had arrived in Belfast in 1854 at the age of 23. He used his fine engineering training to become by 1861 a partner in the firm. There were great days ahead in the making of its liners for the White Star, the Royal Mail, and the Union Castle lines, plus its work for the Admiralty during the War.

In addition to the oil tankers, they built whaling ships, cargo vessels, passenger ferries, bulk carriers. They employed 7,000. The Queen’s Island Yard, striding the mouth of the River Lagan as it flows into Belfast Lough, has been a major force in world shipbuilding. The new dry-dock is capable of building two quarter-million tonners simultaneously.

Each of Harland & Wolff’s gigantic cranes search the skies. Goliath broke the skyline in 1969 at 348 feet high and 460 feet wide. Samson is the second giant of Krupp-Ardelt design. The two cranes loom over Belfast like modernistic mobiles. They are powered by electricity generated within the crane. Steel from British Steel Corporation is uploaded at a special Quay in the Musgrove Channel.

Stories about the workforce are legion. There is this question: “How many men work at Belfast shipyard?” “About half of them,” came the reply followed by their raucous laughter. It was discovered by some that a bakery close to the Yard had installed similar time clocks. For a time wives and girlfriends were able to clock out their men at the required time. Weekly wages were 36 shillings made up to five pounds by working Friday night and all day Saturday. Seventeen men died during the construction of the Titanic.

The worst marine disaster in history took place on a bitterly cold night in 1912 with the sea like a millpond as the lookout strained to see by the light of the stars. Suddenly, he gave the warning, “Iceberg right ahead.” And First Officer William Murdoch reacted immediately, ordering the ship “hard starboard” and throwing the engine into reverse. The warning was too late. There was a grinding noise “like a thousand marbles being dropped.”

The impact lasted 10 seconds. Two hours forty minutes later, the Titanic was at the bottom of the Atlantic, 4,000 feet down. With her went 1,500 passengers and crew.

The Titanic had a swimming pool, a squash court, Turkish baths, a gymnasium, a mock Parisian café complete with living ivy and electric lifts. A ticket could cost $4,350 one way. Only the 700 who got to the lifeboats survived.