The Latin form Cleopatra comes from the ancient Greek meaning “glory of her father.” Her adopted title means “goddess who loves her father.”

And so with very little of historic records, we form an opinion. No papyri from Alexandria survive. Almost nothing of the ancient city survives. There is one written word of Cleopatra’s in 33 BC when either she or a scribe signed off on a royal decree with the Greek word ginesthoi, “Let it be done.” Cicero’s letters of 44 B.C., when Caesar and Cleopatra were together in Rome, were never published. Cleopatra bore Caesar’s son. And in the absence of facts, myth comes in, the kudza of history.

Cleopatra’s childhood tutor was Philostratos, and it was he who taught her the Greek arts of oration and philosophy. During her youth Cleopatra presumably studied at the Museum including the Library of Alexandria. Women of that era might buy houses, lend money, or run mills. Cleopatra was well educated and a later chronicler was said that she was to be a “woman who regarded even the love of letters as a sensuous pleasure.”

Cleopatra VII (69 B.C. to 30 B.C.) was queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. She was a descendent of the founder Ptolemy I, a Macedonian Greek general and companion of Alexander the Great. After the suicide of Cleopatra, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. Her native language was Koine Greek and she spoke the Egyptian language.

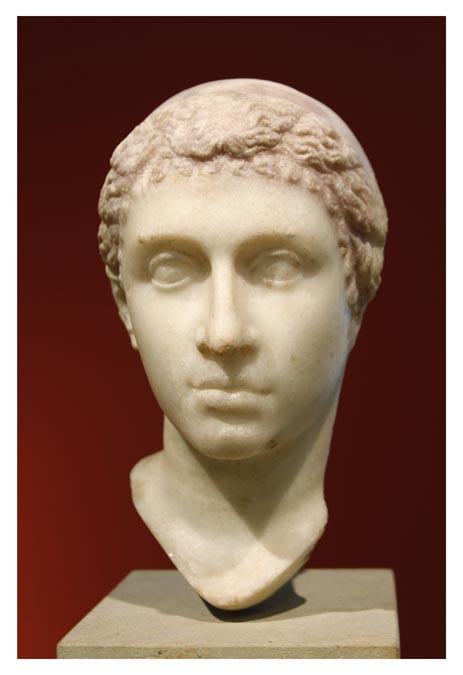

Cleopatra met Mark Antony at Tarsos in 41 BC and began a relationship with him bearing his three children. Her legacy is seen in ancient and modern works of art, Roman historiography and Latin poetry. In the visual arts, her ancient depictions include Roman busts, paintings, and sculptures, cameo carvings and glass, Ptolemanic and Roman coinage and reliefs.

In Renaissance and Baroque art, she was the subject of many works including operas, paintings, poetry, sculptures and theatrical dramas. There is a Hellenistic sculpture which shows two third-century B.C. women playing knucklebones or dice.

Cleopatra was a member of the elite when Rome was a stratified, status-obsessed society. Rank mattered. Learning mattered. Money mattered. And Cleopatra was a subtle and clever guest. It has been suggested that conversations improved with the wine consumed. Then and now, dinner guests of intellectual and seasoned diplomats, sought her attention because she was refined, generous, and charismatic.

Cleopatra’s jewelry was opulent, elaborately worked in gold with insets of coral, lapis, amethyst. and pearl. Abundance flowed hourly to the rich palace from every quarter.

Much of Cleopatra’s scholarship derived from the Arab world where Roman propaganda did not penetrate There she established herself as a philosopher, physician, scientist and scholar. Her name was powerfully resonant. Her competence would be put to the test when disaster followed upon disaster. The Nile River did not stir over the spring of 43 and during that Summer failed to rise at all. Crops failed. Throughout Egypt the misery was acute. Cleopatra steered her kingdom forward with opening the royal graneries to distribute free wheat. Venal tax collectors were denied and exemptions were given to petitioners for relief. She posted notices of amnesty widely.

Cleopatra was a remarkably capable queen, canny and opportunistic, a strategist of the first rank. “What woman, what ancient succession of men, was so great,” wrote an author of a Latin poem which positions her as the principal player of that age.