“Player with railroads and the Nation’s freight handler” —Carl Sandburg

Railroads were freighted with destiny.

Flumes of white smoke over the Rockies became the main symbol of the United Sates and its achievements. The nervous panting, that pam-pah, pam-pah, now slow and even, now hurried, came directly from the soul of the locomotive, as sentient as any human.

By team, lake, river, freight, the Michigan Central got into Chicago by 1852. Daniel Webster wrote the charter for the new company. In Aurora a Mr. Wadsworth, merchant, decided that an 1850 charter to build a little 12-mile road to West Chicago from Aurora ought to be utilized to build a railroad.

Second hand scrap iron was used for the rails. A second-hand engine, a passenger coach and six freight cars, borrowed or rented, were all they could afford. Mr. Wadsworth had been in Boston buying goods when he met John M. Forbes, the father of the Burlington. The Aurora line was a sturdy infant, grew gradually, and reached out its hands for that caravan of freight going westward to Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota.

The “CB and Q” (Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Company) was born in Aurora and employed 2,000 workers at its peak, men strong of muscle, long of wind, steel of backbone, who worked for a dollar and a half a day. Railroad passenger cars, dining and specialty cars, were produced in Aurora. The first Vista Dome car, a prototype, was built in Aurora. Thundering through the city constantly were trains on their way west to build a country.

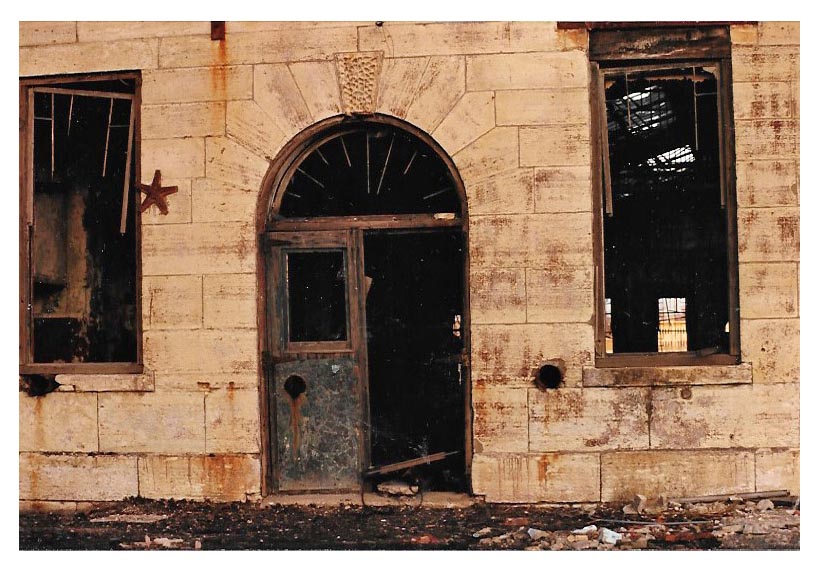

Aurora’s rich railroad history is embodied in the Roundhouse which was constructed in 1856 from limestone quarried in the Fox Valley area. This 19th Century architectural giant featured vaulted ceilings, keystone archways, limestone construction, and skylights.

On 56 acres just north of downtown Aurora, the Roundhouse had been designed by Levi Hall Waterhouse and built by R.J. Coulter Builders. This 40-sided building is made from a precisely cut stone bearing wall on the exterior and an elegant iron loggia around the interior court which support the fascinating complexity of timber roof trusses and iron rods.

The roundhouse had stalls for 30 engines, backshop, paint, and carpenter, shops. With its railroad, Aurora was a link in the colossus which had formed a chain of rails in and out of Chicago. John Cheever wrote that “A railroad station is a human symbol, striking architectural poetry, about our passages together. The station is a gloomy and brilliant example…that means to express the mystery of travel and separation.” There we say hello and goodbye. There we part company with loved ones.

The grand prodigious days of the railroads are mostly memory. Stations that were alive, throbbing, dynamic terminals of our comings and goings are no longer charged with the urgency of life. Author Eugene Kennedy wrote that “Train stations are sacred places where we part and where we come together again. They are points of mystery, crossroads, and terminals…at which we can sense what we value.”

The Aurora Roundhouse has been a gift for posterity. This architectural and historic landmark still has shadows of its past, telling us to appreciate its traditions and heritage. If we listen closely, we can hear the thunder of its past. It is the oldest limestone roundhouse in the USA and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Henry David Thoreau wrote in “Walden” that “When I hear the Iron Horse make the hills echo with his snort of thunder…it seems to me as if the earth had got a race now worthy to inhabit it.”