“New feet within my garden go. New fingers stir the sod. A Troubadour upon the Elm, Betrays the solitude.” —Emily Dickinson

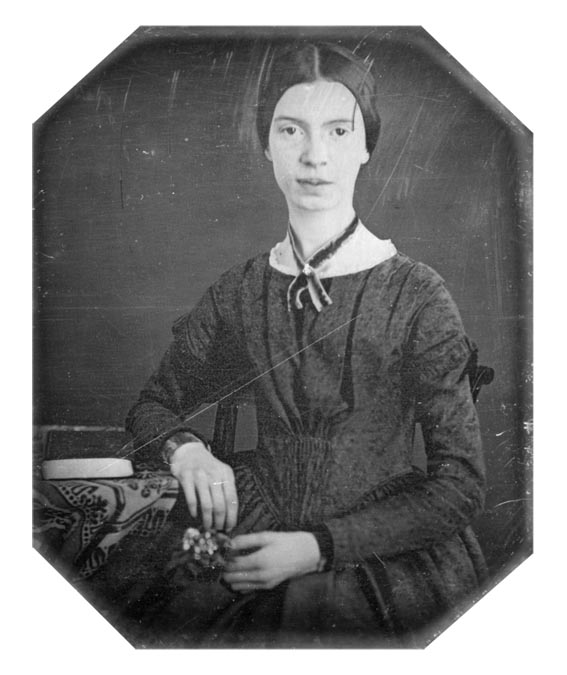

Poet Emily Dickinson created in her writing a distinctively elliptical language for expressing what might be possible, but not yet realized. The literary marketplace offered new ground for her work toward the end of the 19th Century.

The first volume of her poetry was published in 1890, four years after her death. It was met with a stunning success. In less than two years, there were 11 editions and now she is known as an important American poet read around the world.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born in Amherst, Mass. December 10, 1830. Her father, Edward, was a lawyer of high ambition. Little is known of her mother, except that she is often represented as the passive wife of a domineering husband. Emily studied at Amherst Academy for seven years and briefly attended Mount Holyoke prior to returning to her family home. She lived the remainder of her life mostly in isolation.

She became a recluse who wore mostly white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests, or later in life to even leave her bedroom. She never married and most friendships depended entirely upon correspondence.

She was a prolific writer and had only 10 poems of her 1,800 poems published during her lifetime. Her poems contained short lines, typically lacked titles and often used slant rhyme as well as unconventional capitalization and punctuation. Many of her poems dealt with themes of death and immortality. Two recurring topics in her letters to her friends, her poetry explored aesthetics, society, nature and spirituality. Her fascination with naming, her skilled observation and cultivation of flowers and her carefully-wrought descriptions of plants are evident in her poetry.

It was not until her death in 1886 that her sister Lavinia discovered her cache of poems that her work became public. In 1861 she wrote “Hope is the thing with feathers” as a lyric poem in ballad meter and was included with 19 other poems published in 1891.

Emily enclosed flowers in her letters and shared some of Spring’s abundance gathered from her garden. Once she sent pussy-willows with the enclosure that read “Nature’s buff message left for you in Amherst. She had not time to call.” On cold winter mornings walking about, she kept a potato in her pocket to keep her fingers warm.

In addition to studying botany, Emily began collecting flowers to create a herbarium, a collection of pressed dried plants. It was a popular hobby at that time.

Roses were one of her favorite flowers based on their frequency in her letters and poems. In one letter a dried rosebud was hand-stitched on to the page. She called her bouquets “nosegays” and would make them in creative circles. A tiny note was found wound around the stem, carefully concealed from view.

Summer was her favorite season. She mentions it more than any other. There are 145 references to summer in her poems, whereas Winter tallies a mere 39 mentions.

In the 1860s her eyesight began to fail. When her condition stabilized, according to her narrative, she, “did nothing but comfort her plants, till their small green cheeks are covered with smiles.” The care she lavished on plants was a balm to her soul.

Emily Dickinson died May 15, 1886 at the age of f56 from kidney disease. Her funeral was held at the home parlor four days later. She was dressed in white with violets and a pink lady’s slipper orchid at her throat. She was buried in her garden.